A Story from Into the Eye of the Setting Sun

“I am not sure, but I think we were somewhere in Blackfoot country when a large number of Snake Indians came up to us. They were greatly excited and their horses were covered with sweat that lathered and ran down their legs. The Indians kept looking and pointing at a cloud of dust that we could see in the distance. Then they pointed at the powder horns carried by our men, held out their own and turned them up to show that they were empty, and then pointed to the rapidly approaching cloud of dust, and said over and over again, “Cheyenne! Cheyenne!”

By signs, and a few words that our people could understand, the excited Indians made it clear that a band of Cheyennes was coming. The Cheyennes and the Indians who were begging for powder were at war, and it was a war party that was coming with the cloud of dust in the distance.

Our men were foolish perhaps, but they gave the Indians what powder they needed. As soon as they got it, they wheeled their horses and galloped away to seek shelter and wait for the Cheyennes to come within range. A number of our men went to a nearby hill and waited to see the battle.

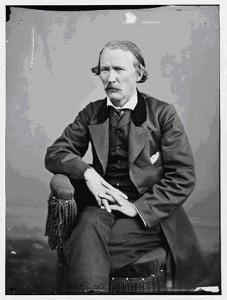

John Freemont

The cloud of dust was coming toward us straight as a crow flies, and it was coming very fast. Our people knew that the Cheyennes were a dangerous, bloodthirsty tribe and the more cautious ones were uneasy, for the war party had drawn near enough for us to see that it was a large one. Nearer and nearer they came, then we saw the war party with whom we had divided the powder join them, and they all came on together.

The men who had gone to watch the battle hurried back to the wagon train, and orders were given for the wagons to draw up in close formation. Guns were loaded and everything was made ready for an attack. In a few minutes the horsemen galloped up to us, and we saw that they were a company of United States soldiers. It was John C. Fremont and his men whom the Indians had mistaken for a warring tribe.

In Fremont’s report to the Washington [D.C.] government, he mentioned the trouble between the Snake and the Cheyenne Indians, and also made mention of seeing our Emigration. His was a topographical map-making expedition, and the maps — made, of course, without the aid of surveys — seem to me to be amazingly complete.

It was on his second expedition that he followed our Emigration for a time. When our people saw that he traveled in a carriage and with seeming comforts as compared to our jolting, lumbering wagons (he was even said to have a rubber sheet to keep himself and his instruments dry, and other such luxuries), some of the emigrants appeared to resent it. They made disparaging remarks, and grumbled because public money supplied such great comforts.

Kit Carson

At that time he was a Brevet Captain of the Topographical Engineers, and not as well known as he was after the Mexican War. I remember him because I was looking for a band of Indians when he came up to us. Kit Carson was with him.

Father had known Carson somewhere else, and everyone had heard of him. There was not a red-blooded boy in our Emigrations but had played at being Kit Carson, the Indian Scout. Everyone was glad to see him. He ate supper with us and sat for a long while by our campfire. As a crowd gathered around, he told us many things about what we would find farther on, and advised about camping places, directions and suchlike.

I remember him very distinctly. I thought of him as being very tall, but rather slight. He wore a broad-brimmed gray hat, very old and battered, and a buckskin suit (I remember that it was heavily fringed up the outside seams). He was a hero to me, and I was determined to not miss a word that he said. He had fine, kindly eyes that crinkled at the corners when he smiled at me.” [pages 25-26]

(From Wikipedia) — In 1842, Frémont lead his first expedition. Carson was his guide. “Fremont’s report was published by the U.S. Congress. The Frémont report “touched off a wave of wagon caravans filled with hopeful emigrants” heading west. Frémont’s success in the first expedition lead to his second expedition, undertaken in the summer of 1843, which proposed to map and describe the second half of the Oregon Trail, from South Pass to the Columbia River.” … “Carson’s services were again requested. This journey took them along the Great Salt Lake into Oregon, establishing all the land in the Great Basin to be land-locked, which contributed greatly to the understanding of North American geography at the time.”

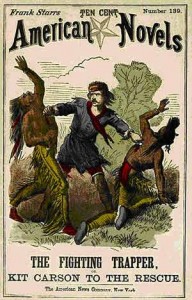

Cover of novel featuring Kit Carson

JOHN C. FREMONT John Charles Frémont (Jan. 21, 1813 – Jul. 13, 1890) an American military officer, explorer, the first candidate of the Republican Party for the office of President of the US, and the first presidential candidate of a major party to run on a platform opposing slavery. Briefly he was military governor and US senator from CA. He was territorial governor of Arizona for 3 years.

Many places are named for Frémont, including: counties in Colorado, Idaho, Iowa, and Wyoming; cities in California, Michigan, Nebraska and New Hampshire; streets in Las Vegas, Minneapolis, Kiel, WI, Manhattan, KS, Portland, OR, the California cities of Monterey, Seaside, Stockton and San Francisco, and the Grant City section of Staten Island, New York; as well as numerous geographical features and Portland’s Fremont Bridge.

KIT CARSON Kit Carson (Dec. 24, 1809 – May 23, 1868) was an American frontiersman. The legend of Kit Carson has continued to grow through the years through dime novels, poems, movies (4 silent and 3 talking), television, and comic books. These fictional tales portray Carson as a heroic figure slaughtering two bears and a dozen Indians before breakfast, and when mixed with a few real historic events, the result is that Kit Carson becomes larger than life.

There are cities named after Carson in California, Colorado, Nevada, and New Mexico.